Dr. Maria Fadiman was there when an African medicine man tried to heal a crying baby by tying a necklace made of baobab tree bark around her neck. She was there when the Amazonian indigenous people were drinking potions to throw up (because it was a cultural tradition) –– and she had to stick a plant down her throat to join them. She’s had to trudge through mud, and down to a river in a rain forest, just to wash her face –– all in the name of ethnobotany. But when she’s not studying plants and making friends in far away countries, she teaches world geography at FAU. Dr. Fadiman spoke to us in her office, amid her dissertation and the books she’s written about foreign plants, with the football stadium outside the window. We got to hear the stories, and see the spunk that keeps students captivated in the classroom.

UP: In addition to your work at FAU, you’re an ethnobotanist. Can you explain what exactly ethnobotany is?

Fadiman: “Ethno” is people and “botany” is plants. So ethnobotany is really the relationship between people and plants. And that can come in all kinds of forms. A lot of people think of it in terms of going somewhere far away — for medicinal, for fibers, for food, for spiritual reasons. And we’re also connected to plants all the time here. [Points to desk] This is plastic, but there’s probably some wood smashed up under here. Whatever you had for breakfast was probably something that came from plants. So we’re all really connected to plants. I do tend to do my work way out in ‘the boonies’, but you don’t have to.

What kind of work do you do out in ‘the boonies’?

What I concentrate on is the use of plants and sustainability. So I try and look: are there ways for people to use their plants and keep the plants growing, so they don’t have to use them up? And part of my particular interest is when people really use a plant and really get connected to it — whether it’s utilitarian or spiritual, or whatever it is for them. The idea of maintaining the ecosystem in which that plant grows. So for me, the ultimate goal is overall conservation through people’s connection with plants. But then also, people are losing their allure about plants. This information is being lost with every generation, so I’m partly trying to record it, so it’s not lost. I used to work a lot more with medicinal plants – now I work more with fibers – but what I would do then was draw the plants, write it, put it in their language in Spanish, and give them back a book of their own information. And then they could choose!

When did you decide you wanted to do this long term?

I was in college and I always wanted to work with conservation, but I didn’t want to do science. I figured science was scary. So I wasn’t sure how to make that all work, but I was taking a class and I learned about the word “ethnobotany” –– people and plants –– so I realized I can put that together. During my junior year of college, I went to Spain my first semester, and the second semester, I spent a quarter in Mexico and a quarter in Costa Rica, as a guide. I didn’t know anything about the rain forest because I was determined not to do science, but I could speak Spanish. So I was helping translate for rail guides, but while I was there, I learned about the plants and bugs. I’m like, ‘That’s science? Well, that’s cool! I can do that!’

When you were studying, where did you want to work? What was your dream job?

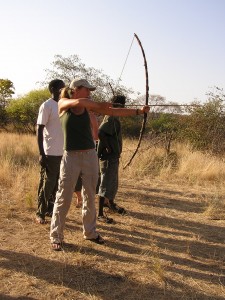

When I first started and went for my interview for my PhD., I wanted to work for a non-governmental organization. And then when I was a TA (teaching assistant) and started teaching lab sessions, I loved teaching and thought it was really fun. And then I realized, ‘Oh, I do want to be a professor!’ And I also get my summers where I go do my research, and go to the Amazon, or to Africa or somewhere cool.

What are the most exotic places you’ve been to, and some memories from those places?

Well, the Amazon is certainly exotic, although I’ve been to Latin America so many times, it doesn’t change that it’s still really exotic. And I was in Tibet two summers ago, and we were riding on this motorcycle all the way to the top of this mountain, and I mean, it’s just like in the movies or the posters. You just see these mountains going off and off, and there are little flowers growing everywhere, and yak are walking around, and these nomadic people who move their tents every few months are greeting me and giving me yak milk. And it’s just these moments where I’m like, ‘Am I really here?’

Do you incorporate some of these stories in your classes?

Yes! Absolutely. Every time I come back from a trip, I look at my pictures, and I look at what can I incorporate where. [There] are lots of my own stories, too. I try to make it come alive when I’m in the classroom.

Students are fascinated by you, and they love your style of teaching. Some even rated you as “hot” on RateMyProfessor.com.

You know, I didn’t even go on there earlier, but now I know — I’ve got the chili pepper. Cool beans!

What do you think it is about your style of teaching that students like?

Well, besides the chili pepper aspect, I think one thing is — I really like doing it. And I like when students respond and I get their take on things. In a big lecture class, it’s hard to be inclusive but I try as much as possible. But also, I really try to make it real, and that’s my biggest thing. When I say, ‘Here’s the [European Union]’or ‘Here’s the environment in Latin America,’ and then I say, ‘And here’s my experience when I was there and something that happened to me.’ So they say, ‘Wow, that’s a real place and those are real people and it matters.’

In 2006, National Geographic named you one of their ‘Emerging Explorers.’ How did this all happen?

Well, it was my second year [here], and I got some email from National Geographic and I opened it, and it said: ‘Hi, I’m not sure if you got our first email but you’ve been chosen [to be] a National Geographic Emerging Explorer. Here’s a grant, we want you to come to the main offices, etc, etc. I was like, ‘Did I apply for a grant and totally forget? Did they make a mistake?’ I had no idea what this was, but I wanted it and I was super excited. So there was a number and I called and she said, ‘Are you calling to see if it’s real?’ And I said, ‘Yeah, yeah,’ and she said, ‘Well, it is.’ And I said, ‘Woo hoo!’ Apparently I was nominated anonymously and they go through a whole committee and voting process. And I was one of the people chosen, and it’s so exciting. I know lots of people could have been chosen just as easily who do really interesting work, but I got it, so I’m excited!

What has your life been like as someone who does this kind of work?

[sighs] Well, exciting and kind of living in a fantasy in so many ways. When I go out to the Amazon, and I’m with an indigenous person and we’re walking through the rain forest, we’re hanging up a hammock and walking down to the river to wash my face, I just sometimes can’t believe that this is where I am. It was a fantasy as a child and I always wanted to just go out there. And now it’s like, ‘Wow, I’m really here and I have a reason for being here and I really, really want this to stay alive – these people and this land.’ And I’m getting to do that, so it’s super exciting. But it’s hard, you know? My blisters are all popping, and my feet are bloody, and I got all kinds of parasites, and I’m tired and stuck in the mud. And sometimes I say, ‘Wow, I would just like a pizza and a nice couch.’ But it’s also opened my eyes.

You tell students these stories so that it’s more real to them?

Right. And my idea is that I want people to care about the whole world. Yes, I’m into the Amazon and all that, but to get that, of course, we’re all very different and that’s exciting. But also, at some level, we aren’t and that’s what I want people to get. It’s all connected and we’re all connected, and I’m like everyone else in a lot of ways. If I have this experience, it can happen to anyone.

What’s been the most exciting part for you as a professor?

I think partly how satisfying it is to teach, because I really wasn’t headed to be a professor. It’s the excitement of getting to share what I know and care about. And that I really care about what other people think and do. I wanted to save the world and be out there with an NGO, and now I try to awaken in other people some of these ideas.

I found out that you were quoted on a Starbucks cup. How’d that happen?

Once National Geographic puts you on a list, life gets pretty cool. I got an email, but I didn’t know what they were talking about, but I just said yes. And later on, since I don’t drink coffee, I went out and looked through the garbage can for a Starbucks cup. One of my friends and colleagues saw me and said, ‘What are you doing?’ And then she got me a Starbucks cup and it was a quote from a basketball player, and I was like, ‘Okay, now I get it.’ So I wrote a first quote, and they wrote back saying they needed one for a bigger sized cup.

What inspired you to write the quote that ended up on the cup?

I realized my life is really exciting and connected to travel and the world, but that’s not what makes life an adventure. You don’t have to come to Africa to have life be this exciting. You find people you connect with. You don’t have to go to the Amazon. Talk to your neighbor or immigrants that live near you. All that can be done here. Whatever you’re doing, just do it fully.