Dressed in a bright orange T-shirt as colorful as his personality, senior second baseman Mike Albaladejo is ribbing third baseman/outfielder Devon Workman as they leave their Minorities in the Media class to head back to the locker room.

Dressed in a bright orange T-shirt as colorful as his personality, senior second baseman Mike Albaladejo is ribbing third baseman/outfielder Devon Workman as they leave their Minorities in the Media class to head back to the locker room.

It is a blistering hot Monday afternoon, a day set aside for weight lifting, and Albaladejo is quick to remind Workman that his lower body needs work.

“When are you going to get rid of those chicken legs?” he jokingly asks, pointing to Workman’s calves fellow teammates teammates and fellow classmates Alex Hudak and Jeremy Strawn start cracking up.

“Hey, hey. We can’t all be like you and just eat Wendy’s all day,” Workman says of Albaladejo’s regimen.

“So?” Albaladejo says with a sheepish grin as he takes a sip from his yellow Wendy’s cup. “That’s my diet and I’m sticking to it!”

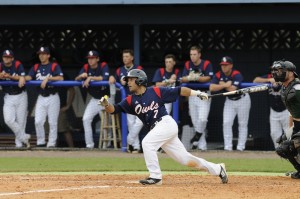

Albaladejo’s mouth is as loud as the sound his bat makes after one of his team-leading 33 hits. Being just 5-foot-7 does not hinder the fiery Puerto Rican from having the biggest voice on the squad.

“I’m thinking, ‘Who is this little Spanish kid that does not shut up?’ I’m playing center and this guy just does not stop talking. Even behind the dish I can hear him,” Hudak says of his first encounter with Albaladejo in summer league ball as teammates with the Leesberg Lightning four years ago. “He’s just loud and flashy. You really can’t not notice Mike.”

He may not be team captain, but Albaladejo is the glue that holds the locker room together.

He uses his voice to keep the team in-line on the field, but also to keep them loose of it.

As he lies on his back on the soft blue carpet of the locker room while untying the orange laces of his black Nike sneakers, Albaladejo and a handful of players are watching the Phillies-Tigers game on television. An unsuspecting Miguel Cabrera gets beaned in the face attempting to field a line-drive hit, as blood spews from his eye.

“Ready, wait for it, wait for it, Boom!” Albaladejo says as he mimics the replay, capturing the exact dazed expression Cabrera had, as the room roars with laughter.

With a little over two months left in his college career, these are moments Albaladejo cherishes. He says being away from his family in Winter Park, Fla has been difficult, but that his teammates are like his brothers.

Albaladejo describes his family as “blue collar.”He admits to being a momma’s boy, but his passion for baseball comes from his father Netalli, a former standout high school catcher in Connecticut.

“That’s where I get it from,” Albaladejo says proudly. “From an early age, he gave me the passion to play baseball.”

Albaladejo was born when his parents were 19 years old, so his father quickly abandoned his dream of professional baseball to take care of him.

“I commend him on that. It takes a man to do that,” Albaladejo says. “He pushes me and keeps me humble. He always tells me to remember where I come from. Because the road to where I am now was not easy. We’re not rich, but we’re not poor. We work hard for everything we need.”

Albaladejo received offers from seven other schools. He says the final decision came down to FAU and FIU.

As we walk towards the Oxley Center to head to the weight room, I ask him how close he was to signing with FIU.

“Real close,” Albaladejo said. “That was a big choice for me. I remember talking to Mac on the phone before my freshman year. He really sold me. I wanted to impact a team right away and that’s why I chose FAU.”

Albaladejo did just that, helping the team win the Sun Belt as a sophomore. His favorite memory is his 13th inning walk-off three-run homer against Western Kentucky in the Sun Belt tournament that year.

“We’re very proud of him,” his father says. “Not being tall, he’s always had a chip on his shoulder, but he’s always exceeded everybody’s expectations.”

That doesn’t stop Albaladejo’s father from sharing a secret about his son. Horror films turn the confident Albaladejo from man to mouse, the latest being Paranormal Activity.

“He loves scary movies but when he comes home he’s a wimp. He’ll sleep with the light on,” his father jokingly says. “It’s just funny to see him watch these movies and come back all paranoid.”

His father bursts out into laughter at the thought of his son, a public communications major, ever being shy, even during his childhood.

“Oh, you always know when Mike is in the room, definitely,” his father says . “Going back to middle school and high school, he always had that charm and personality that people love.”

Especially when he’s crooning as if he was auditioning for American Idol in the locker room and during bus rides. Even if his teammates mock him for it.

“He’s a guy in the locker room that’s a jokester, a prankster,” Hudak says. “He loves to sing. He thinks he’s got a real good voice, but just talking to Mike you know that it’d be really bad if he tried to do some vocals.”

Making his teammates laugh is as natural to Albaladejo as the shift to second base after spending last year as catcher. Coach John McCormick came up with the idea in the fall as a way to save his legs for the upcoming season, and he was impressed with the results, appreciating the sacrifice Albaladejo made for the sake of the team, which is currently without Hudak and Robert Buckley.

“I think he’s handled it great. He’s doing us a big service. We’ve had a lot of guys injured,” McCormick says. “He said ‘no problem, coach’ and he’s worked at it. I think he’s become a pretty good second baseman. Over the years, if you look at the league, he’s become, I don’t know if he’s at elite status yet, but he’s a pretty darn good college second baseman.”

Albaladejo got a head start on the process during the offseason.

“The past couple summers in the Florida Collegiate League I’ve played second base, so I know how to make plays and field ground balls,” Albaladejo explains. “It’s a lot more thought process than with catching.”

Thinking before speaking is the biggest difference McCormick sees in Albaladejo from his freshman year to the present. Now, McCormick says Albaladejo has a filter.

“In my years here, he’s clearly one of the most vocal guys we’ve ever had and I’ve been around,” McCormick says. “When Mike got here, because he was an emotional guy, he would say and do things because of that. To be able to listen to what’s going on, digest it, and then be able to make a comment, as opposed to just blurting out what he feels and what he thinks. I think he’s been able to process information and make better decisions.”

Off the field his choices have improved as well. The life of a college baseball player can get hectic. Albaladejo points out the struggles of being a student-athlete, admitting that his freshman year was overwhelming.

“It’s not as easy as people think,” he says. “There’s so much time involved with baseball that it takes away from school. It’s hard to balance that out. It’s tough when right after class you come to lift weights, then hit, and every day is practice, then we have games. Especially Wednesday, in that class you were just in, we have a test. On game day when we play Miami, we have a test, so the transition is not easy, but it definitely is rewarding.”

Now it is Albaladejo that is using his experience to offer advice to younger players on how to adjust to the transition from high school to college. He states his maturity level has risen vastly in the last four years.

“Setting my priorities straight about what really matters in life. That’s what I’ve learned. School and education and the people that care about you are the most important things. Everything else is just distractions,” Albaladejo says. “There’s a lot of temptation out there. A lot of negative things out there in college. You’re on your own basically. I don’t have my parents out here to make choices for me. I’ve learned right from wrong a lot better.”

He takes a pause and looks away, almost as if to reminisce on his time at FAU, before speaking some more.

“I wouldn’t have it any other way. It’s been a blessing,” Albaladejo says. “It’s been great learning how to balance both of those out.”

The little man will continue to pursue his goal of playing in the big leagues, but if he doesn’t make it, he has another plan.

“I hope I’ll have a chance to play some professional baseball, if not, I’ll get my degree this spring and work somewhere with public relations,” Albaladejo says. “Use my speaking skills to my advantage.”

He and his team walk out of the weight room dripping with sweat, his voice by far the loudest of the bunch.

John Ramos • Apr 10, 2012 at 8:44 pm

Get off his nuts. He’s not even good. WAKE UP